By Leah Marie Gonse and Michael Palocz-Andresen

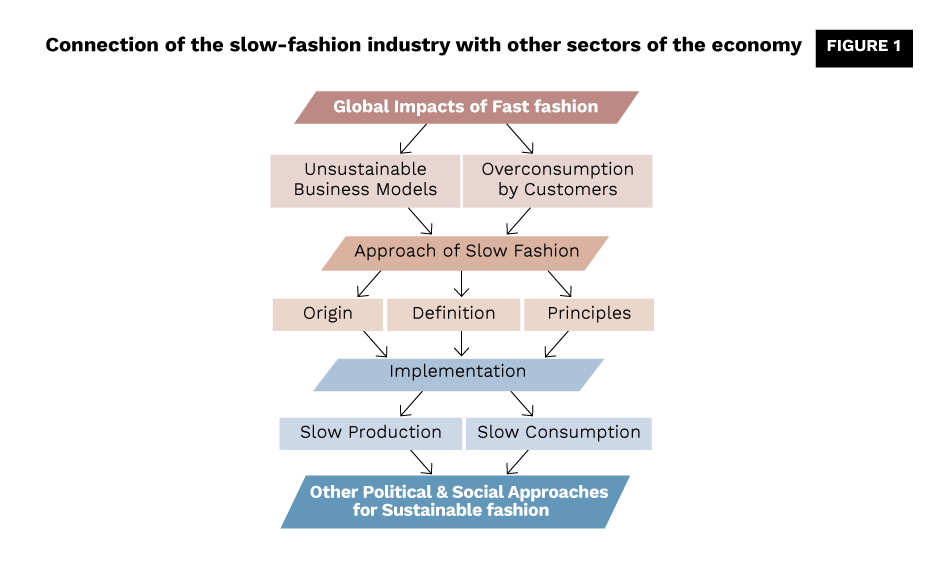

The fashion industry operates on a mostly unsustainable business model that focuses mainly on growth of sales and revenues. However, these practices have drastic negative impacts on the environment, workers, and animals. The slow-fashion approach offers a sustainable alternative. This paper analyses in depth all the aspects of slow fashion and how they can complement each other to make progress towards a sustainable fashion industry.

Fashion has become increasingly a way to express one’s taste in apparel while keeping up with the current fashion trends. Consuming fashion has broadly become an activity which most do without questioning it. Fashion brands attract their customers by advertising with new trends and low prices. Such fashion brands are often associated with the term “fast fashion”, as they try to upscale sales through the fast creation and output of new clothes for consumers to buy.

However, the textile industry is the second-largest water polluter. A single pair of jeans requires around 7,000 litres to produce1. The fashion industry is responsible for around 1 billion tons of CO2 emissions per year2. If these practices are continued, many parts of the environment, biodiversity, and natural habitats will be destroyed. There is a need for the leaders of the sector to analyse the consequences of keeping production costs low.

The concept of slow fashion represents an alternative approach to fast-fashion practices. Slow fashion advocates a sustainable fashion industry with respect to people and the whole environment by suggesting fashion production, as well as fashion consumption, that is based on different values. It has grown increasingly into a global movement, which can be witnessed in Canada, Germany, and Thailand2.

This paper explains the concept of slow fashion in depth, as well as its origin and current development around the globe, in order to demonstrate how the fashion industry could operate on the basis of fair and sustainable practices.

This paper explains the concept of slow fashion in depth, as well as its origin and current development around the globe, in order to demonstrate how the fashion industry could operate on the basis of fair and sustainable practices.

Figure 1 shows the connection of the slow-fashion industry with other sectors of the economy.

International Comparison of the Impacts of Fast Fashion

In terms of fashion production and consumption, different countries are differently affected by the impacts.

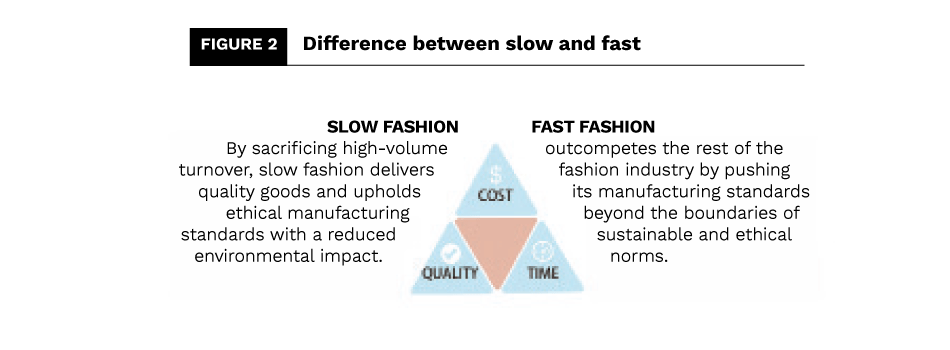

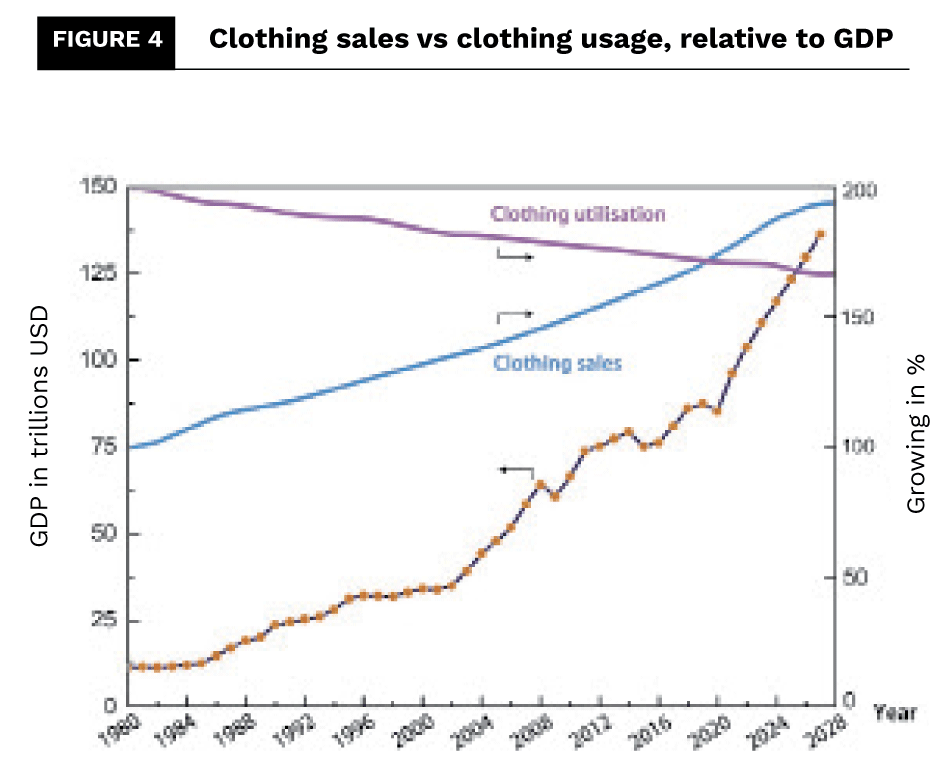

The fashion industry is based on patterns of high consumption. This means that the business model of most fashion brands relies on the consumer’s continuous demand for new clothing to buy. To increase revenues, vendors are willing to release new collections in short periods of time. Additionally, these clothes are sold at low prices, which encourage customers to buy in large quantities. However, these low prices can only be realised by using cheap materials for their products. Thus, many garments are low in quality. This means that fabrics are prone to damage, which forces customers to throw the textile away. Fast fashion is focused on rapidly bringing high quantities of mass-produced and cheap fashion items to stores worldwide3. These practices can be observed especially in the global West. Fast fashion attempts to continuously grow sales by playing on the customers’ unsatisfied demand for new clothing by constantly creating new trends.

To keep production costs as low as possible, most Western fashion brands outsource their production and manufacturing steps to countries in the global south and Asia. The workers in the factories have to bear the true cost of low prices for customers. Often, brands expand to countries like Bangladesh, but also China, Vietnam, or Indonesia, for clothes production4. These countries have very low environmental standards, as well as poor work conditions. The workers are mostly women. However, many female children are forced into illegal child labour in factories to financially support their families.

Sewing workers earn about €40-80 a month4. These wages are not enough even to cover their expenses or basic needs. In addition, the workers must deal with an unsafe work environment with a risk of a range of accidents, like collapsing buildings or outbreaks of fire. One of the most commonly known examples is the catastrophic collapse of the Rana Plaza production building in Dhaka, which killed over 1,100 people5. But even on a daily basis, workers are exposed to dangerous chemicals and substances which are known to be toxic to human health.

As the fashion industry operates all around the globe, resources and goods have to be transported over long distances. The fashion industry produces more than 1 billion tons of CO2 a year6, which accounts for even more than the airline and shipping industries combined. In total, about 10 per cent of the CO2 emissions in the world are produced by the fashion industry.

Additionally, the fashion industry is the second-largest user of water. A single pair of jeans requires around 7,000 litres of water. However, this makes the industry also the second-largest water polluter. Chemicals are used to create certain attributes, such as dyes in order to achieve a certain colour. These chemicals are then released into the waters. Certain Asian lakes are known for repeatedly changing colour during the day due to chemicals.

Cheap clothing is mostly produced from synthetic fibre, such as polyester, which is not decomposable and breaks down into micro-plastic. Therefore, textile waste is very harmful to nature, as it releases micro-plastic into the water cycle. These materials also make it difficult to recycle resources. As a result, clothing is mostly disposed of in waste landfills. Particularly in non-Western countries, unused clothing largely ends up in the trash, as there is a lack of alternative ways to use the materials. Thus, Eastern countries are forced to collect the waste of Western countries in landfills, such as in the Atacama Desert in Chile7. As a result, valuable resources finish up as rubbish, consisting of synthetic fibres harm nature.

The Origin of Slow Fashion

Slow fashion is part of the umbrella term “sustainable fashion”. Slow fashion describes an approach that attempts to make the fashion industry more eco-friendly. It provides alternative practices to the commonly used methods in the fashion industry.

The idea of this concept was triggered largely through an increasing awareness of the harmful and unsustainable processes used by most fashion brands. During the last decade, journalists and authors have been researching in depth the impacts of global fashion production and consumption. This has exposed the highly resource-intensive and unsustainable practices of most fashion brands. A famous example is the 2019 book The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion by Elizabeth L. Cline, who is a clothing resale expert. This book reached millions of readers globally and made consumers aware of the negative impact of industrial fashion activities. Through this arose the demand for a change in the fashion industry. As a result, the first developments of alternative and sustainable approaches like slow fashion have emerged.

The expression “slow fashion” is credited to Kate Fletcher. Fletcher is a research professor, as well as an author and consultant in the fashion industry. In 2007, her paper “Slow Fashion: An Invitation for System Change” coined the term “slow fashion” as it is understood today, as a concept for the sustainable production and consumption of fashion.

From then on, the slow fashion movement gained further recognition. The concept has served as a framework for many fashion brands in recent years to develop creative, sustainable business models as alternatives to fast fashion.

The Meaning of the Term “Slow Fashion”

As mentioned, Kate Fletcher gave the term “slow fashion” its meaning by comparing it to the slow food movement, which was popular at that time. The concept of slow food was derived from the increasing consumption of fast food. It was meant to portray the opposite of the growing, globalised fast-food culture. But, with time, slow food has become more than solely a movement against fast food. Slow food describes a different underlying set of assumptions and values. It rejects the common economic processes of large-scale, mass production. Slow food has grown into a business model that represents broader goals and values. It tackles the common production and consumption practices by valuing long-existing traditions, as well as social and environmental goals. These include local production, fair employment, diversity, and sustainability 8.

The slow-fashion movement was created on the same basis. It started as a culture promoting the slow movement in fashion and has developed into something beyond. Slow fashion is not the opposite of fast fashion. Slow fashion does not stand for fashion produced and consumed at a slower pace without the negative social and environmental impacts. Slow fashion challenges the common business practices and underlying values. As fast-fashion business models are based on the assumption that there is eternal economic growth, the approach of slow fashion is based on a different worldview.

Fast fashion requires high product throughput in order to upscale profits. Thus, most fashion brands operate in an attempt to achieve constantly improving growth and efficiency, which means keeping all costs as low as possible. Slow fashion describes a broader vision of fashion activities based on quality, sustainability, pleasure, and cultural diversity8. Therefore, slow fashion operates from a different starting point. It requires a different infrastructure in order to fulfil the underlying values and goals. This concept is a complete repositioning of strategies and designs, as well as production and consumption practices.

Figure 2 shows the difference between slow and fast fashion.

Additionally, transparency is made a priority. There are an increasing number of conscious buyers who demand that companies be completely open about their methods of production. Brands should be transparent with their production measures and materials to ensure eco-friendliness and high quality. Success is not measured solely by economic growth. Slow fashion sees fashion in a global context and reshapes the economic concepts, such that development towards slow cultures can be seen across different industries.

Additionally, transparency is made a priority. There are an increasing number of conscious buyers who demand that companies be completely open about their methods of production. Brands should be transparent with their production measures and materials to ensure eco-friendliness and high quality. Success is not measured solely by economic growth. Slow fashion sees fashion in a global context and reshapes the economic concepts, such that development towards slow cultures can be seen across different industries.

Principles of the Concept

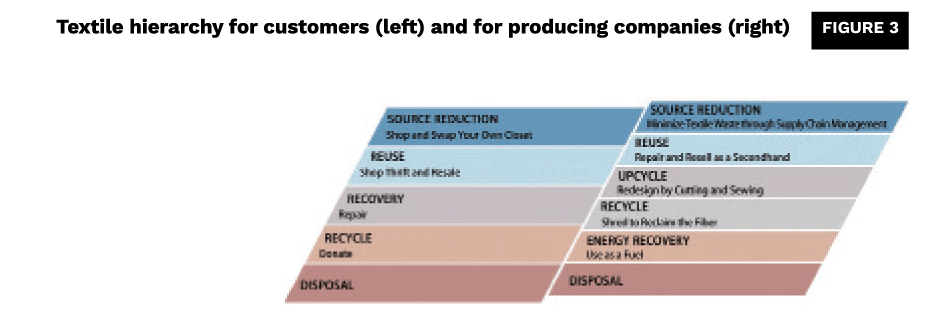

Slow fashion is based on two main beliefs. First of all, clothing is not viewed as a disposable good. Textile products are not meant to end up in a trash can at some point. All materials should be reusable. Secondly, the predominant belief is based on quality, rather than quantity. As producing clothing is resource-intensive, the materials and resources used should be carefully sourced and not have to go to waste 9.

Figure 3 shows the difference between the considerations of the customers and those of the producing industry in the textile hierarchy.

This indicates two very important aspects for producing slow fashion. Clothing production should be done in a way that it allows the longest-possible lifecycle. If items are not wearable any more, they should be repaired, reused, or repurposed. So fashion should be properly designed to ensure longevity in terms of quality and wearability. Fashion brands should pay more attention to the materials and fabrics used. This ensures that the clothes are made with the highest quality available and only the most eco-friendly materials are processed. All other business processes should be in line with the most sustainable and harmless practices as well.

Thus, slow fashion is rather based on local production, which means supporting local manufacturing and being close to the customer. New clothing should not be produced in an attempt to set new trends. It is not economically driven by sales, but takes a broader view of the fashion industry, taking people, animals, and the environment into account.

Slow fashion is taking intentional, holistic business actions which preserve the earth’s ecosystem. In more detail, this means that slow fashion holds accountable not only the production of clothing, but also its consumption. It advocates a change from the customer and industry perspectives. This means that fashion is viewed as an embedded part of its environment which takes responsibility for its impact beyond the purchase. Hence, slow fashion also requires a change of shopping behaviour on the part of the consumer. So slow fashion provides not only strategies for manufacturing, but also a shift in consumer behaviour. Hence, all the characteristics of slow fashion can be viewed from the production and consumption perspectives to provide guidelines for sustainable fashion.

Implementation of Slow Fashion

The principles of the slow-fashion concept can be translated into common strategies and practices to ensure sustainable production and consumption. The term “slow fashion” is constantly being reshaped by new innovations and developments in fashion. Thus, there is no set definition of the implementation. It rather provides a framework that can vary depending on individual perspectives. Nevertheless, there are certain widely used values and characteristics.

As slow fashion has grown into a global movement, there are certain consumption practices associated with following slow fashion. Additionally, there has been a significant increase in new fashion brands with the objective of producing in a slow-fashion manner. If companies choose to produce clothing according to this approach, there are certain prerequisites, in order that slow fashion may be further evaluated from the standpoint of consumption and production. In addition, these provide guidelines for customers who are trying to buy slow fashion.

Implementation of Production

First of all, production needs to rely on quite small quantities, so that fashion brands can drastically reduce waste due to unsold clothing. To take it even one step further, many companies have been adapting to an on-demand manufacturing model. An example is the Merz b Schwanen brand, which starts production only after the required quantities have been ordered by sales agencies10.

Further, new collections need to be released purposefully, without focusing on trends or unusual designs. Commonly collections are only released around twice a year. Many slow-fashion brands focus on one winter and one summer collection to design seasonally appropriate clothing. Other brands take it even further and only produce one collection per year. A rather extreme example is the Swedish brand ASKET, whose whole product line is based on one single collection being sold at a time [10]. This means that every piece ASKET produces has to be closely designed to identify the best possible garments, serve a timeless style, and comply with all other requirements before being incorporated in the overall collection.

The result is that ASKET makes use of another common and important aspect of the slow-fashion culture, starting with the design of clothing. Fashion should be designed in a timeless manner, not influenced by trends. Timeless designs make clothes wearable for a long period of time, which should prevent the consumer from becoming disenchanted with clothes as personal preferences or trends change. This reduces the likelihood of consumers keeping unworn pieces in their closets or producing unnecessary textile waste. Clothing should be made for longevity. Thus, the design process is crucial for creating sustainable fashion.

Fashion design should also include choosing long-lasting and eco-friendly materials. Firstly, this reduces the chance of any damage occurring to the clothing, and of producing more textile waste on landfills. Secondly, even if the clothes are damaged, it is worth repairing or reusing the materials. In this regard, commonly used resources for slow fashion are linen or organic cotton from small, sustainable producers. The Merz b Schwanen brand goes as far as producing their own fabric from yarn to ensure the sustainable origin of their products. For this, the brand reuses machinery that is over 100 years old, so-called round knitting machines, which was used back in the time when the Swabian Jura was known for being an important fashion production area in Germany.

It is not widely known that fashion was once based on regional manufacturing before globalisation made it so easy to outsource production to lower-wage countries and ship goods around the world. Slow fashion is about going back to local manufacturing to reduce carbon emissions due to extended transport channels for resources or finished clothing. Additionally, it reduces the damage done to the environment and people in production areas. Slow fashion supports working with local artisans for fair wages. Slow fashion strongly advocates not only environmental sustainability, but also social sustainability. Firms should provide fair, ethical, and appropriate work conditions for all the workers they employ. Workers should not be exposed to harmful substances or working in dangerous conditions. The sewing workers of Merz b Schwanen consist of one artisan family that is also located in the Swabian Jura. This allows Merz b Schwanen to work closely with their partners in a friendly work atmosphere without having to span long distances.

Production measures like these make it possible to drastically reduce pollution and unburden communities in low-wage manufacturing countries of the negative impact of fast fashion. In addition, this should enable fashion to cater for regional and cultural designs and production methods. These characteristics try to incorporate a focus on more specific production while making use of purposeful actions throughout all business processes to ensure resource-saving practices. This enables fashion production methods which protect the environment and communities, as well as releasing fewer carbon emissions into the atmosphere. This is an important aspect that contributes to the preservation of our planet and the fight against climate change.

However, slow fashion is not defined simply by creating new fashion production methods or changing existing ones to the slow-fashion manner. The fashion industry also needs to explore alternative business models to make fashion and clothes available to customers other than by buying newly produced clothes. This is a partial explanation for the huge increase in vintage and secondhand shops that can be commonly observed around the world. There is a rising awareness of how resource-intensive it truly is to produce fashion from new resources. This changes the customer’s perception of buying new clothing and increases the demand for alternative business models to make fashion accessible.

Figure 4 compares clothing usage and clothing sales, relative to world GDP.

The increase in secondhand outlets applies not only to shops but also to online platforms. For example, the online marketplace Mädchenflohmarkt, or “girl jumble sale”, is a fashion shopping website which sells only vintage and secondhand clothing 11. They offer clothing that has been sent to them by customers who want to sell their clothes.

The increase in secondhand outlets applies not only to shops but also to online platforms. For example, the online marketplace Mädchenflohmarkt, or “girl jumble sale”, is a fashion shopping website which sells only vintage and secondhand clothing 11. They offer clothing that has been sent to them by customers who want to sell their clothes.

Another example is the rise of other alternative fashion platforms or shops where clothing can be shared or lent for a certain period. These concepts are increasingly gaining customers. In this model, customers do not buy new clothes, but share existing ones. The most prominent example is fashion companies that have a variety of clothes which can be borrowed by the customer for a certain period. Often these companies do not even produce their own clothing, but offer items from existing brands. Other brands do produce the clothing themselves but only offer them for rent.

Customers can use this service either by paying per item rented or by having a subscription to a show which allows them to rent a certain number of items per month. This business model is aimed specifically at customers who want to borrow clothes for special occasions, since it may frequently be unnecessary and unsustainable to buy something new to wear for a single event. There is a growing number of very individual renting business models for fashion. Fairnica is a website where consumers can rent a whole capsule wardrobe12. A capsule wardrobe describes the purposeful collection and composition of clothes which can be combined in multiple ways to create the most-possible outfits for different occasions, while using a relatively small number of items.

Implementations for Consumption

However, the slow-fashion movement is not only about a different business model on the industry side. The impact of clothing is not only considered up to the point of sale, but goes beyond by encouraging sustainable consumption behaviour on the part of customers. Slow fashion advocates conscious consumption, which is as crucial as purposeful production. As is commonly known, the fashion industry is also driven by the demands of customers. Thus, it is a critical part to make consumers aware of how resource-intensive clothing production is and who truly pays the prices for cheap clothing. Consumers have to stop the fashion lifecycle of buying clothing in large quantities for low prices, which is often worn a couple times before ending up as textile waste.

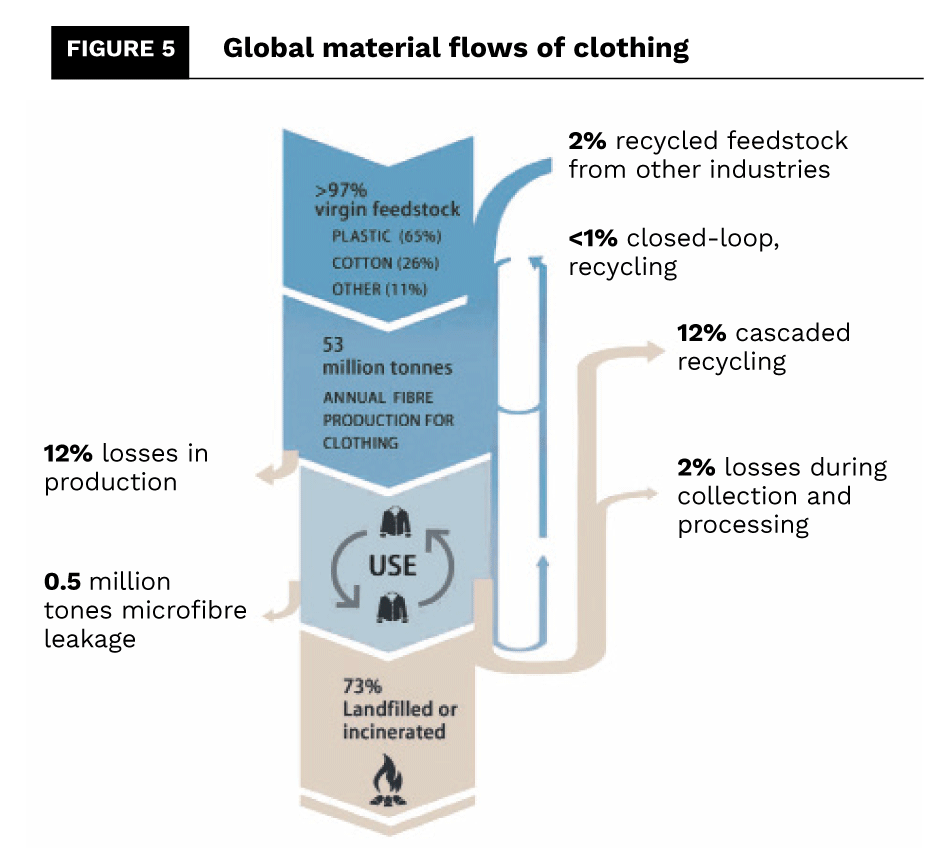

Figure 5 shows global material flows for clothing in 2015.

Therefore, a behavioural change on the customer side is very important in order to make the fashion industry sustainable. This means there has to be a mindset change towards fashion consumption, called the slow-consumption philosophy. This philosophy goes further than simply reducing consumption by buying fewer clothes. Slow fashion reincorporates the active making of fashion on the customer side, which changes the current power relationship between producer and consumer. The philosophy is based on the belief that the best purchase is no purchase.

Therefore, a behavioural change on the customer side is very important in order to make the fashion industry sustainable. This means there has to be a mindset change towards fashion consumption, called the slow-consumption philosophy. This philosophy goes further than simply reducing consumption by buying fewer clothes. Slow fashion reincorporates the active making of fashion on the customer side, which changes the current power relationship between producer and consumer. The philosophy is based on the belief that the best purchase is no purchase.

The consumption mindset focuses on wearing existing clothes as long as possible, as well as possibly not buying new items, especially not trend-driven items. Consumers should keep in mind that they should buy clothing only if it is necessary, it suits one taste, and they can imagine themselves wearing it for a long time. Ideally, the consumer should develop an emotional or cultural connection to the clothing. This does not apply only to buying new clothes, but also to any consumption of clothes.

Consumers can try to consume fashion by using already-existing clothing to honour the materials used. It should be bought secondhand before looking for new items. Consumers should actively look for alternative ways to access fashion, apart from buying it. Such a development can be seen within Bangkok’s night markets. A growing number of designers and secondhand retailers are developing an alternative fashion culture by bringing their own visions of fashion and designs straight to customers in flea markets13. Customers should make use of such alternatives and support locally growing markets.

Also, existing offers like sharing or lending services need to be tried out. Such methods can also be utilised in a private context by sharing clothes with friends or family. Clothes that are not being used any more should only be repurposed or upcycled. Fashion can be much more than buying clothing from the brands that offer it. Fashion can be made individually by shaping clothing according to one’s taste. This can be done by actively sewing clothing or modifying items that are no longer used. In the case of clothing, it should be sold or given away. In this way, slow fashion reincorporates a mindset of resourcefulness and ethics for all people, as it reminds customers of the work and resources that go into creating clothing by creating an emotional connection with the textile.

Generally, customers should focus on buying fewer clothes less often. When there is a need for new clothing, they should first try to look for alternative ways before buying new. If the decision is to buy new, it should be high-quality and produced in as resource-saving a way as possible.

Political and Social Aspects of Slow Fashion

Through the growing global awareness of the unsustainable practices employed by the fashion industry, there are an increasing number of agreements, committees, NGOs, and regulations to shift fashion towards sustainable operations. The so-called Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action is a coalition of fashion brands, suppliers, and retailers that addresses environmental impacts by aiming at net-zero emissions by 205014. The signatories consist of over 40 leading brands, such as H&M and Burberry.

All these labels have committed to reducing 30 per cent of CO2 emissions by 2030. This charter gets global support from many related associations and committees. Examples include the China National Textile and Apparel Council and the Sustainable Fashion Academy, as well as the Global Fashion Agenda. The Global Fashion Agenda is an initiative which provides a forum for supporting sustainable actions. Additionally, in 2020, the Circular Fashion System Commitment was introduced to guide towards circular business models and strategies.

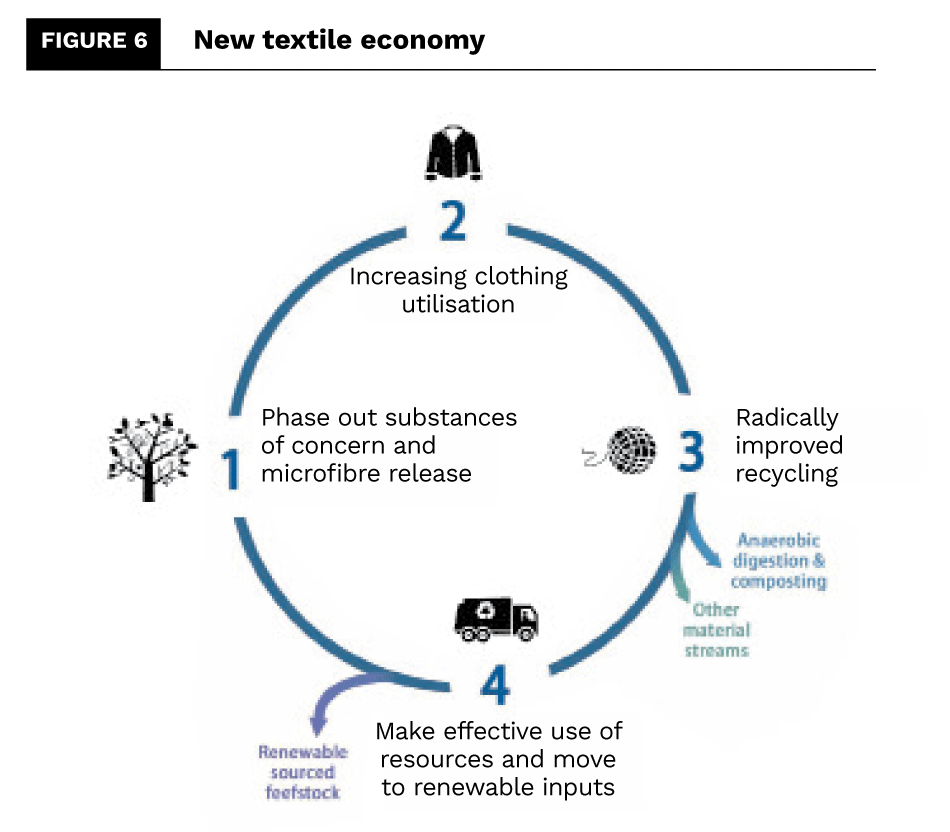

A similar approach can be seen within the European Union regulations. In 2018, the EU passed regulations to convert the linear economy into a circular one. The circular economy package contains regulations for various production methods, products, and materials. These also concern the fashion and textile industry. By 2030, all textile must be recyclable15. Accordingly, clothing is required to be designed in a way that allows easy recycling. Further, textiles must contain a certain amount of recycled fibre. Triggered by the global pandemic and the outbreak of war, the EU is increasingly taking action to implement these regulations in order to stop today’s throwaway society.

Figure 6 shows the idea of creating a new textile economy.

Summary

Most fashion brands currently operate on the basis of an eternal growth model, in which upscaling sales is the main focus. To gain a constant increase in revenues, the fashion industry makes use of low-quality materials, as well as unsustainable practices. The environment and workers in production areas pay the true price of the industry’s actions.

Production is often outsourced to countries in the global south and Asia, where working conditions and environmental regulations are poor. Wages are not enough to cover the expenses of living, factories are often subject to accidents, like fires or collapsing buildings, and workers are exposed to harmful chemicals which damage their health. These substances are often disposed of into nature, harming the environment and natural life. Outsourcing requires a lot of transportation routes between brands, factories, and customer. The fashion industry is responsible for around 10 per cent of the yearly CO2 emissions blown into the air.

Slow fashion represents an alternative approach to the common business practices. It is a movement that advocates a sustainable fashion industry in production and consumption. This concept is based on a broader worldview which views fashion within the context of the whole ecosystem. Slow fashion considers fashion from a different starting point by operating on broader values than solely economic growth. Fashion should take responsibility for its impacts and resources beyond the purchase. In slow fashion, clothing is not viewed as a disposable good. This means that textile should not go to waste, but rather be reused, recycled, or repurposed, either by companies or directly by the customer. The conscious consumption philosophy of slow fashion lays responsibility on the consumer side as well. This leads to a change in power relations between industry and the customer. Therefore, brands need to explore new business models to make fashion accessible.

However, besides slow fashion, there are various other movements and developments towards a sustainable fashion industry. In industry, as well as on the consumer side, there is an increasing awareness and demand for more sustainable fashion business models and a shift in customer behaviour towards more resourcefulness.

Outlook

Over recent years, the sustainable and ethical fashion sector has been growing rapidly and continues to do so. Since 2015, this sector has grown by 8.7 per cent annually. The fashion and beauty apps with the most downloads in the United States in 2021 are shown in figure 7.

Growth is especially driven by customers’ demand for sustainable options. Through the increasing awareness of fashion’s negative impacts, many consumers are willing to change their behaviour. The Boston Consulting Group conducted a survey which revealed that over half of the mostly American respondents buy from more social and eco-friendly brands, if possible 16.

A survey carried out by McKinsey, focusing on Spain, the UK, and Germany, suggests that over 60 per cent would stop or reduce buying from brands which are associated with treating workers unfairly. In particular, the pandemic enforced positive developments towards a more sustainable fashion behaviour, especially on the consumer side 17. Around 57 per cent of German respondents claimed to have made significant behavioural changes to reduce their personal impact. More customers are making use of recycling or repurposing clothing, while reducing fast-fashion consumption. Nevertheless, brands, too, are increasingly engaging in implementing sustainable and social measures. The Higg Index, which measures companies’ engagement in social and environmental 18, has reported an annual increase of 15-19 per cent in such measures.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr Roberto Carlos Ambrosio Lázar, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Facultad de Ciencias de la Electrónica, Indentificación y Control de Parámetros de Clúster de Instrumentos Automotriz, for years of support in this scientific area.

About the Authors

Leah Marie Gonse is currently in the sixth semester of her studies in International Business Administration & Entrepreneurship at the Leuphana University. She is especially passionate in topics of sustainability and innovation. She aspires to finish her bachelor’s degree in 2023. Subsequently, she is planning to further deepen her knowledge with a master’s in business administration.

Leah Marie Gonse is currently in the sixth semester of her studies in International Business Administration & Entrepreneurship at the Leuphana University. She is especially passionate in topics of sustainability and innovation. She aspires to finish her bachelor’s degree in 2023. Subsequently, she is planning to further deepen her knowledge with a master’s in business administration.

Michael Palocz-Andresen is working as a full professor at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla México. Since 2018 till 2022 he was a Herder-professor supported by the DAAD at the TEC de Monterrey. He became a full professor at the University West-Hungary Sopron, and a guest professor at the TU Budapest, the Leuphana University Lüneburg, and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is a Humboldt scientist and an instructor of the SAE International in the USA.

Michael Palocz-Andresen is working as a full professor at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla México. Since 2018 till 2022 he was a Herder-professor supported by the DAAD at the TEC de Monterrey. He became a full professor at the University West-Hungary Sopron, and a guest professor at the TU Budapest, the Leuphana University Lüneburg, and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is a Humboldt scientist and an instructor of the SAE International in the USA.

References

- Wahnbaeck C. et al.: Wegwerfware Kleidung/Throw Away Ware Clothing. 2015. https:// www.greenpeace.de/sites/www.greenpeace.de/files/publications/ 20151123_greenpeace_modekonsum_flyer.pdf. (24 May 2022)

- Fashion Revolution Singapore: Fashion Sustainability Report. Fashion Revolution Singapore. 2021. https://issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/final___fashion_sustainability_report_2021 (25 May 2022)

- Tun, Z.T.: H&M: The Secret to Its Sucess. Investopedia. 2021. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/041216/hm-secret-its-success.asp (31 May 2022)

- Sinplastic: Fast Fashion – Auswirkungen auf die Umwelt/Fast Fashion – Impact on the Environment. 2020. https:// sinplastic.com/fast-fashion-umwelt-auswirkungen/#10_ausbeutung_von_mensch_tier (25 May 2022)

- International Labour Organisation: The The Rana Plaza Accident and its Aftermath. 2018. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/geip/WCMS_614394/lang–en/index.htm (23 May 2022)

- Mcfall-Johnsen, M.: The fashion industry emits more carbon than international flights and maritime shipping combined. Here are the biggest ways it impacts the planet. Business Insider. 2019. https://www.businessinsider.in/science/news/the-fashion-industry-emits-more-carbon-than-international-flights-and-maritime-shipping-combined-here-are-the-biggest-ways-it-impacts-the-planet-/articleshow/71640863.cms (31 May 2022)

- Averre, D.: The fast-fashion waste mountain: Gigantic pile of clothes including Christmas sweaters and ski boots looms over desert in Chile – a symbol of how the industry is polluting the world. MAILONLINE. 2021. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10190155/The-fast-fashion-waste-mountain-Gigantic-pile-clothes-looms-desert-Chile.html

- Fletcher, K.: Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Journal of Fashion Practice. 2010; 2:259-66. https://doi.org/10.2752/175693810X12774625387594 https://www.businessinsider.in/science/news/the-fashion-industry-emits-more-carbon-than-international-flights-and-maritime-shipping-combined-here-are-the-biggest-ways-it-impacts-the-planet-/articleshow/71640863.cms (31 May 2022)

- Clark, H.: SLOW + FASHION—an Oxymoron—or a Promise for the Future…? Fashion Theory The Journal of Dress Body & Culture. 2008; 4:427-46. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174108X346922 (14 May 2022)

- SWR: Slow Fashion – stylish und langlebig/Slow Fashion – stylish and long-living. 2021. https://youtu.be/7_6ZjAv2thM (15 May 2022)

- ARTE: Die Modeverweigerer/ The Fashion Rejecters. 2021. https://youtu.be/j0ycWZJU6Fc (18 May 2022)

- Fairnica: Über uns/About us. 2022. https://fairnica.com (15 May 2022)

- The Landmark Bangkok: 6 Night Markets to visit in Bangkok. 2020 https://sukhumvit.landmarkbangkok.com/shopping/5-night-markets-to-visit-in-bangkok/ (31 May 2022)

- United Nations Climate Change: Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action. 2021. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Fashion%20Industry%20Carter%20for%20Climate%20Action_2021.pdf (31 May 2022)

- Bonse, E.: Mehr Secondhand für alle/More Secondhand for everyone. 2022. https://taz.de/EU-Paket-zur-Kreislaufwirtschaft/!5841754/ (25 May 2022)

- Global Fashion Agenda; Boston Consulting Group; Sustainable Apparel Coalition: Pulse of the Fashion Industry. 2019. http://media-publications.bcg.com/france/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry2019.pdf http://media-publications.bcg.com/france/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry2019.pdf (31 May 2022)

- McKinsey & Company: Survey: Consumer sentiment on sustainability in fashion. 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/ Survey%20Consumer%20sentiment%20on%20sustainability%20in%20fashion/Survey-Consumer- sentiment-on-sustainability-in-fashion-vF.pdf (23 May 2022)

- Sustainable Apparel Coalition: The Higg Index. https://apparelcoalition.org/the-higg-index/ (31 May 2022)