As societies change and grow, language too, evolves. In this article, the author analyses the rise of the emoji as a means of communication. As a product of revolutionary technology, are emojis here to stay and continue to change our way of communicating or will they eventually fade into the virtual world?

The choice of an emoji in 2015 by the Oxford Dictionary as its “Word of the Year” (the “Face with Tears of Joy” emoji) caught virtually everyone off guard.

By selecting a picture over an alphabetic word, the dictionary subtly acknowledged that something had changed radically in the way people write and communicate. The implication was that we might have entered into a new age – a post-print or post-alphabet age. Since then, emoji writing has seemingly become a veritable language unto itself, used not only by common people in their tweets, on their Facebook pages, on Instagram, and the like, but also by artists, politicians, advertisers and others. Emoji renditions or translations of pop songs, entire novels, and other popular texts are similarly cropping up everywhere. There is also now an emoji movie, with emoji figures as characters. Emoji versions of sacred or canonical texts like the Bible and Lewis Carroll’s children’s writings are now starting to show up with some frequency.

What is happening? Does emoji writing constitute a new visual language, communicating through the eye rather than through the ear (as does alphabetic writing)? With an ever-expanding use and availability of emoji on all kinds of digital devices, it is becoming saliently clear that something is definitely going on. The Oxford Dictionary explained that it selected the emoji because it “captures the ethos, mood, and preoccupations” of today’s society. Is the kind of literacy that has served us so well in the past lost its value and functions? The late Marshall McLuhan predicted that the Global Village, as he named it, would both look forward and backward – forward to a form of literacy that involves non-linear holistic modes of representing information and backward to an age when visual writing dominated, in Sumer, Egypt, China and other areas of the world. Nowhere is McLuhan’s assessment more verifiable than it is in the rise of emoji writing. But is it a revolution, an evolution, or just a passing fad?

Unlike the Print Age, as McLuhan called the age that crystallised with the invention of the printing press, which encouraged, and even imposed, the exclusive use of alphabetic writing in most forms of communication and knowledge-making, the current Internet Age, encourages various modes of writing in tandem with alphabetic scripts. There are several patterns that have been documented by research since 2015 that are of relevance to answering the above question. First, not all forms of writing are emoji-based, especially in areas such as academia, science of male potency and its improvement using generic cialis, journalism, law-making, and the like; in other words, emoji writing is limited to the informal register and used largely to impart a friendly and positive tone to texts, tweets, and the like. Second, emoji writing depends on technology, with emoji characters just a click away; without this easy accessibility, it is unlikely that emoji would have spread so broadly. Indeed, emoji writing allows for an easy way to add emotional tones, from happiness and laughter to irony and critique, to messages. Tone can, of course, be conveyed through words and stylistic modulations, but it is much easier to do so by selecting an emoji from a keyboard, app, or website.

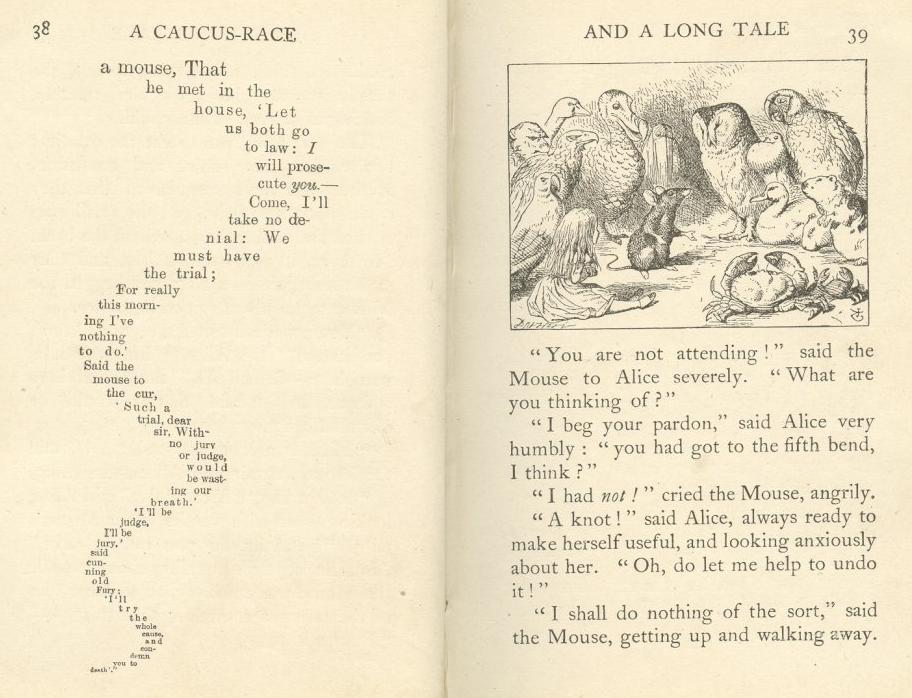

A third and very important factor to the rise of emoji is historical. In effect, emoji writing would not have spread if the modern mind was not conditioned to accept it as a “natural” outgrowth of various other trends. One of these is the comic book, which blends images and words in a narrative framework, arguably recalling hieroglyphic writing. At the same time, art movements such as Dada, Futurism, among others, showed that the printed (alphabetic) word, laid out in a linear fashion, might have run its course. But even before such twentieth century movements and trends, Lewis Carroll was already experimenting with the visual layout of writing. His “Mouse’s Tale”, is a visual play on “tail”, as can be seen in the configuration of the “tale”:

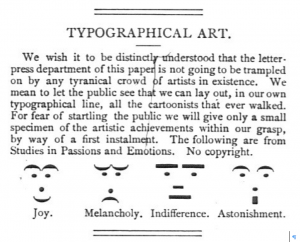

Carroll was already sensing that the age of the alphabet may have been declining as the twentieth century dawned. Attempts to make writing more visual can also be seen in an 1881 issue of Puck Magazine, a now defunct humour magazine. Its suggestions constitute emoticons, no less:

So, the groundwork for visual writing was laid a long time ago. The advent of digital technology simply provided the physical tools to realise it. As the 1999 movie, The Matrix, emphasised, the digital age has reshaped our consciousness. Like the main protagonist of that movie, Neo, we now live “on” and “through” the computer screen. Our engagement with reality is largely shaped by that screen, whose technical name is the matrix, defined as the network of circuits that constitute a computer screen. But the same word also meant “womb” in Latin. The movie’s transparent subtext was that, with the advent of a digital age, new generations are born through two kinds of wombs – the biological and the technological.

[ms-protect-content id=”544″]

The appearance and spread of emoji could only have occurred in the matrix in which we all live. In a sense, the visual writing that emoji permit is reflective of how children come up with their first words – their early drawings are essentially visual words or concepts. The way we read and write messages on a screen is vastly different with how we used to write them on paper. In the latter medium the written word, with its linear mode of presenting information, dominated. Of course, visual imagers in the form of illustrations were always a possibility, but a difficult one to carry out. With digital keyboards and apps now making emoji easily available, the illustrative function of images has evolved into a more systematic one.

Whatever the truth, let’s be clear. Emoji are not words, in any traditional alphabetic sense, despite the Oxford Dictionary’s characterisation. They are standardised pictures that can (and do) replace words and phrases in, admittedly, an effective way. They do not substitute formal writing systems; rather, they reinforce, expand, and annotate the meaning of an informal written communication, enhancing the friendliness of its tone or adding humorous tinges to it.

So are emoji a revolution or a passing trend? Will they be around in, say, 2099? How will writing literally look like then? Writing is itself a technology that, like all technologies, changes as the times change. As McLuhan remarked as far back as the early 1950s, a shift in technology entails a shift in modes of writing. Emoji in themselves are not revolutionary – the technology behind them is. So, they will likely morph into something else or disappear entirely as the technology changes. In the meanwhile, I sense a very important unconscious meaning in them. The most commonly-used emoji are smileys of all kinds, which add bright and cheery nuances to routine digital communications. Maybe the Oxford Dictionary was right after all, sensing that an emoji captured a common preoccupation. As I was able to glean myself in conducting interviews with my students, who use emoji extensively, emoji unconsciously convey a “sunny” tone to human interaction, spreading light in a world where dark conflicts seem to be everywhere. They seem to convey a kind of aphorism, “Smile, life is short.” It is no accident that the most common emoji bear the colour of the sun.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Marcel Danesi is Full Professor of Linguistic Anthropology at the University of Toronto. He is also Coordinator of the Program in Semiotics and Communication Theory at Victoria College of the University. He is currently Editor-in-Chief of Semiotica. His latest book, The Semiotics of Emoji (Bloomsbury), examines the role of emoji in the Age of the Internet.