By Mills Soko and Mzukisi Qobo

Global Context

The coronavirus global pandemic has caused significant harm to the global economy. With two-thirds of the world’s population located in developing countries and facing massive economic damage from Covid-19, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has called for a $2.5tn financial package for these countries.[1] Developing countries have borne the brunt of the Covid-19 outbreak “in terms of capital outflows, growing bond spreads, currency depreciations and lost export earnings, including from falling commodity prices and declining tourist revenues.”[2] The impact has been greater than it was during the 2008/9 global financial crisis. Portfolio outflows, for example, from the key emerging economies soared to $59bn between February and March. This is far in excess of the outflows recorded by the same countries at the inception of the global financial crisis, which amounted to $26.7bn.[3]

Compared with the financial firepower deployed by industrialised countries, developing countries have paltry resources to combat the Covid-19 crisis. For example, the United States Congress voted a staggering $2tn stimulus package, while the British government had four major budget announcements within a fortnight. For their part, the Eurozone countries eschewed fiscal austerity in favour of a “whatever it takes” approach.[4] Advanced economies and China have strung together sizeable financial packages aimed at throwing a $5tn lifeline to their economies. These financial measures are calculated to alleviate the physical, economic and psychological effects of the crisis.

Nonetheless, the world economy will go into recession and this will have serious economic consequences for developing nations, with fiscal and foreign exchange constraints tightening further over the course of 2020. Developing countries are projected to face a financing gap of nearly $2tn to $3tn over the next two years. In the absence of monetary, fiscal and administrative capabilities to respond to the crisis, they will have to contend with the twin burden of a devastating pandemic and global recession.[5]

Can Africa Overcome its Challenges?

Africa’s social infrastructure is weak. Many countries are hamstrung by poor health systems, a lack of medical equipment and supplies, as well as inadequate medical personnel to respond adequately to health challenges. The African continent is also susceptible to climate shocks, such as drought, which adversely affect food security. The World Bank (WB) estimates that Africa could face a severe food security crisis, with agricultural production expected to contract between 2.6 percent and 7 percent.[6] The African population suffers deficiencies in terms of low life expectancy, high disease burden, as well as other social ills related to alcohol and substance abuse, insufficient physical activities, and unhealthy diets.[7] Several African countries, including leading economies in the region, are among the worst performers on the Human Development Index.[8]

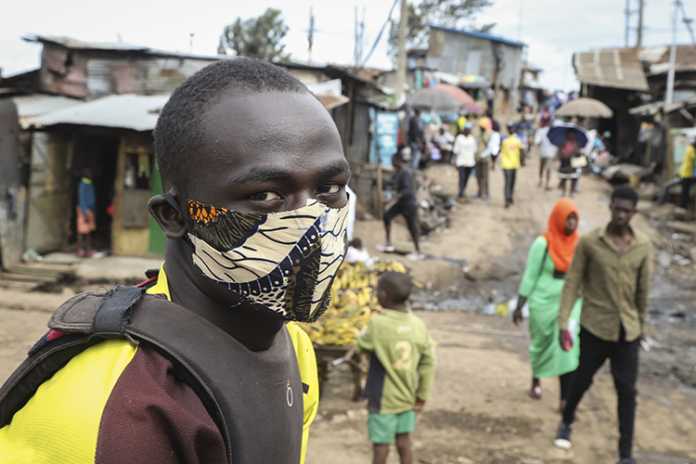

In the context of Covid-19 these challenges are likely to be exacerbated if the infection rates are not curtailed and a vaccine is not found. Social distancing has limits in Africa where population density is very high, and where poor households live in densely populated areas. As the African Centre for Strategic Studies has noted, African countries boast megacities such as Lagos, Cairo, Kinshasa and Johannesburg that have peak population densities greater than that of New York City at 56 000 people per square-metre.[9] The implications of this are that social distancing and extended lockdowns are unlikely to be effective and could ultimately trigger social tensions and popular discontent. There is also a high cost to social distancing as informal traders and small enterprises have to halt operations, creating a potential risk of rise in poverty levels and malnutrition due to a loss of income. Nonetheless, Africa’s youthful population and warmer climate could be an advantage. These attributes, however, provide false comfort and cannot inoculate the continent against the Covid-19 pandemic, especially in light of deep socio-economic vulnerabilities, including food insecurity, malnutrition, lack of access to quality health services, and inadequate provision of water and sanitation, all of which are problems stemming from poor governance. Vaccination is, therefore, the ultimate solution to Covid-19.[10] Until this is discovered, it is important that African countries work hard to coordinate better their programmes, pool their resources, and augment their capabilities. This will put them on a stronger footing in crafting their responses to Covid-19 and seeking development support from external partners.

What Role Can South Africa Play?

President Cyril Ramaphosa is the current Chairperson of the African Union (AU), a role that places him uniquely to lead an effort to coordinate the work of various institutions and financing instruments; forge common African positions; and orchestrate engagements with African external actors, including key bilateral partners and international organisations. At the bilateral level, and working with the AU President, the AU Chair can engage China on the basis of the existing Forum on China-Africa Cooperation to ascertain the type and level of support that China can provide to the African continent during this crisis period. This is also an opportune time to deepen the partnership with the European Union (EU), which has long-standing and chequered ties with Africa dating back to the colonial era.

The EU’s commitment in respect of Covid-19 support measures towards the African continent is commendable but it needs to do more. Only a few countries are beneficiaries of EU support for Covid-19 initiatives. Ethiopia has been offered 10m euros to support the government’s Preparedness and Response Plan. In Nigeria, the EU has pledged 50m euros to support the country’s efforts to fight Covid-19. For its part, Sudan will receive 10m euros to bolster the country’s humanitarian projects related to access to clean water and hygiene. Sierra Leone will benefit to the tune of 34.7m euros to address the economic consequences of Covid-19, including efforts to strengthen macroeconomic resilience and stability. In addition, the EU intends to unveil further measures as part of a renewed EU-Africa Strategy that will be presented at the 2020 EU-Africa Summit in Brussels.[11] The EU has declared Africa its most important global partner. If it is to mean anything, such rhetoric should be backed by serious commitment and concrete actions during Africa’s time of need.

Given its current role as AU Chairperson, and its unique position as the only African country that is a member of the G20, South Africa is strongly poised to play a leading role in developing and lobbying for a common set of African proposals to the global community, including countries such as China that have been expanding their diplomatic and commercial footprints on the African continent over the past two decades. Britain, which has been carving a new role for itself in the aftermath of Brexit, has an opportunity to realise what former Prime Minister Theresa May and current Prime Minister Boris Johnson have characterised as ‘Global Britain’. There is no better time than during this crisis for Britain to project itself as a credible global actor by taking a leading role in responding to pressing global challenges.

The main priority for South Africa is to coordinate a common and coherent African platform with a view to mobilising resources across the continent and to agreeing a collective agenda in terms of engaging with external partners. In the past, Africa has been a passive recipient of largesse from the major powers. Now is the time for the continent to proactively shape its own agenda and present it to the rest of the world. On 3 April 2020 President Ramaphosa convened a teleconference meeting of the AU Bureau of Heads of State and Government to discuss Africa’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.[12] Noting the unprecedented nature of the threat posed by Covid-19 to the continent, the meeting endorsed the operationalisation of the AU Covid-19 Response Fund set up on 26 March 2020.[13]

The meeting emphasised the importance of a comprehensive continental strategy that sets out Africa’s priorities and measures to mitigate the socio-economic and political impacts of the pandemic on African nations. Further, the meeting agreed to set up regional coronavirus task forces in each of Africa’s five regions: Southern Africa, East Africa, West Africa, Central Africa and Northern Africa. These task forces will “oversee screening, detection and diagnosis; infection prevention and control; clinical management of infected persons; and communication and community engagement.”[14]

The Heads of State enjoined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and WB to recast their present disbursement policies to show flexibility and speed, including raising the availability of IMF special drawing rights (SDRs). In addition, they underscored the need for a comprehensive stimulus package for Africa, “including, deferred payments, and the immediate suspension of interest payments on Africa’s external public and private debt in order to create fiscal space for Covid-19 response measures.”[15]

As AU Chairperson, South Africa should champion the kind of mobilisation reminiscent of the 2005 Gleneagles undertaking by the G8 to provide support for Africa’s development.[16] What was significant about that initiative was that it sought to structure a solid platform for a development partnership between Africa and Europe, with the New Economic Partnership for Africa’s Development used by African leaders as the basis for dialogue. As part of this compact, industrialised countries made a collective pledge to double overseas development assistance from the 2004 levels of $34.5bn to $67bn, with 50 percent of this disbursed to Sub-Saharan Africa.[17]

External Partners

The WB and IMF command the largest potential resources to address the economic shocks occasioned by Covid-19. Leaders of both international financial institutions have exhorted creditor countries to suspend debt repayments to enable the poorest countries to spend more on health systems. There ought to be recognition by the advanced countries that their fates are intrinsically linked to those of African countries and they will ultimately inherit Africa’s looming crisis. There also needs to be a coherent and globally coordinated response, rather than the current mixture of ad hoc funding commitments and initiatives.[18] The ratcheting up of financial support to date has not been proportionate to the enormous scale of the Covid-19 threat.

The IMF has stated that it has up to $1tn available globally to help countries manage the financial effects of the Covid-19 crisis.[19] The IMF needs to respond to stem what is poised to be the largest capital flight from developing countries by issuing new SDRs.[20] The IMF’s Managing Director, Kristalina Georgieva, has pointed to the replenishing of funds utilised in a debt relief and aid mechanism during the 2014 Ebola epidemic that broke out in three African countries. There has also been a proposal that principal payments – the actual debt payment, not interest charges – be waived for the most vulnerable countries.[21] For its part, the WB has allocated a $14bn Covid-19 package to shore up beleaguered economies, as well as to support private sector activities through the International Finance Corporation.[22] The WB will require additional resources to be able to provide support through, for example, soft loans and grants.

Multilateral development banks can also provide funds and expertise, especially in assisting the least developed countries in programme development and implementation. As Africa’s biggest trading and investment partner, the EU as well as other major donor partners have ample resources to offer solidarity support and other forms of assistance to African countries. Within the EU, France has been leading European efforts to secure a deal on debt relief for Africa, expanding credit-swap lines and expanding IMF SDRs by $500bn.[23] Regional development banks such as the African Development Bank and the New Development Bank should also be engaged to look beyond specific member country support and to potentially vulnerable regions on the African continent.

Overall, a key challenge for African countries is to present a unified front and outline a clear and consistent set of demands to the international community. Fourteen Latin American and Caribbean countries have already approached the IMF for emergency facilities totaling $4.48bn.[24] Recently the WB approved $50m in instant funding to Kenya to support the country’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, while the IMF approved the disbursement of $109m to Rwanda to help the country deal with its balance-of-payments of problems stemming from the outbreak of Covid-19.[25] There is no common panacea for African countries with distressed economies, but other African nations should seek help and craft solutions that meet their national interests and needs.

About the Authors

Mills Soko is Professor of International Business and Strategy at Wits Business School. His research focuses on business strategy, innovation, international trade, and regional integration in Africa.

Mills Soko is Professor of International Business and Strategy at Wits Business School. His research focuses on business strategy, innovation, international trade, and regional integration in Africa.

Mzukisi Qobo is Head (Designate) at the Wits School of Governance. His research focuses on public policy and governance, geopolitics, and international political economy.

Mzukisi Qobo is Head (Designate) at the Wits School of Governance. His research focuses on public policy and governance, geopolitics, and international political economy.

[1] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, The Covid-19 shock to developing countries: Towards a “whatever it takes” programme for the two-thirds of the world’s population being left behind, UNCTAD: Geneva, 30 March 2020, at https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/gds_tdr2019_covid2_en.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Larry Elliot, ‘Africa won’t beat coronavirus on its own,’ The Guardian, 27 March 2020, at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/27/africa-coronavirus-west-covid-19

[5] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, op cit.

[6] World Bank, ‘For Sub-Saharan Africa, Coronavirus Crisis Calls for Policies for Greater Resilience,’ World Bank: Washington DC, 9 April 2020, at https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/for-sub-saharan-africa-coronavirus-crisis-calls-for-policies-for-greater-resilience

[7] World Health Organisation, The State of Health in the WHO African Region. Geneva: WHO, 2018, at https://www.afro.who.int/publications/state-health-who-african-region

[8] Ibid.

[9] African Centre for Strategic Studies, Mapping Risk Factors for the Spread of COVID-19 in Africa. 3 April 2020. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-risk-factors-spread-covid-19-africa/

[10] Okonja-Iweala, Ngozi, ‘Ebola Lessons in Fighting COVID-19’. Project Syndicate, 1 April 2020. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/africa-ebola-outbreak-lessons-for-covid19-by-ngozi-okonjo-iweala-2020-04

[11] European Commission, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Communication on the Global EU Response to COVID-19. Brussels: European Commission, 8 April 2020, at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/joint_communication_global_eu_covid-19_response_en.pdf

[12] Participants in the meeting were President Abdel Fattah al Sisi of the Arab Republic of Egypt, President Ibrahim Keita of the Republic of Mali, President Uhuru Kenyatta of the Republic of Kenya, President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo, President Paul Kagame of the Republic of Rwanda, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia, President Macky Sall of the Republic of Senegal, and President Emmerson Mnangagwa of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

[13] The Presidency of the Republic of South Africa, From the Desk of the President, 6 April 2020, at https://mailchi.mp/presidency.gov.za/presi-desk-mon6april20

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Elliot, op cit.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Elliot, op cit.

[19] Reuters, ‘The IMF has $1tn war chest for fighting the virus,’ 3 April 2020, at https://www.reuters.com/video/watch/imf-has-1tn-war-chest-for-fighting-the-c-id708033589?chan=8gwsyvzx

[20] Elliot, op cit.

[21] Lucy Lamble, ‘Africa leads calls for debt relief in face of coronavirus crisis,’ The Guardian, 25 March 2020, at https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/25/africa-leads-calls-for-debt-relief-in-face-of-coronavirus-crisis

[22] World Bank, ‘World Bank Group Increases COVID-19 Response to $14 Billion to Help Sustain Economies, Protect Jobs,’ Press Release, 17 March 2020, at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/03/17/world-bank-group-increases-covid-19-response-to-14-billion-to-help-sustain-economies-protect-jobs

[23] Peter Fabricius, ‘France and SA working on plan to help Africa deal with coronavirus pandemic,’ Daily Maverick, 7 April 2020, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-04-07-france-and-sa-working-on-plan-to-help-africa-deal-with-coronavirus-pandemic/

[24] Michael Stott, ’14 Latin American nations to seek IMF help to combat big recession,’ Financial Times, 5 April 2020, at https://www.ft.com/content/dfd1aeed-6d56-466a-be6c-7bb73fc8da23

[25] James Anyanzwa, ‘Bretton Woods’s $159m Covid-19 aid,’ The East African, 4 April 2020, at https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/Bretton-Woods-usd-159m-Covid19-aid/2560-5514004-evy4dgz/index.html