By Emma Saxena and Michael Palocz-Andresen

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused changes in frame conditions that enabled individuals to create new environmental-friendly habits. These hold the potential to support a sustainability transition within the transport sector. This paper illustrates the opportunities that arise from the pandemic and how this might shape a sustainable development in the future.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic currently poses one of the most urgent challenges for human well-being to the world. Measures that were implemented to counteract the expansion of the virus, such as global travel restrictions and stay-at-home orders, have led to tremendous conditional changes for individuals. Daily routines as well as consumption patterns shifted, and remote work became a huge part in the lives of many. As a consequence of such measures and associated behavioural changes on a broader societal level, the impact of the pandemic has led to the most severe disruption of the global economy since World War II1. Many industrial sectors are restrained, which led to a drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in 2020.

The main driver of this development is the transport sector2. In times of human-made climate change which is similarly urgent as the COVID-19 pandemic but is unfolding its consequences in a rather long-term perspective, reducing greenhouse gas emissions drastically is required in order to avert the serious threats global warming is posing to human well-being. Analysing which behavioural changes and mechanisms have led to the drastic reduction of emissions during the pandemic can inform scientists and decision makers about future interventions and policies that target the reduction of the transport sector’s climate impact.

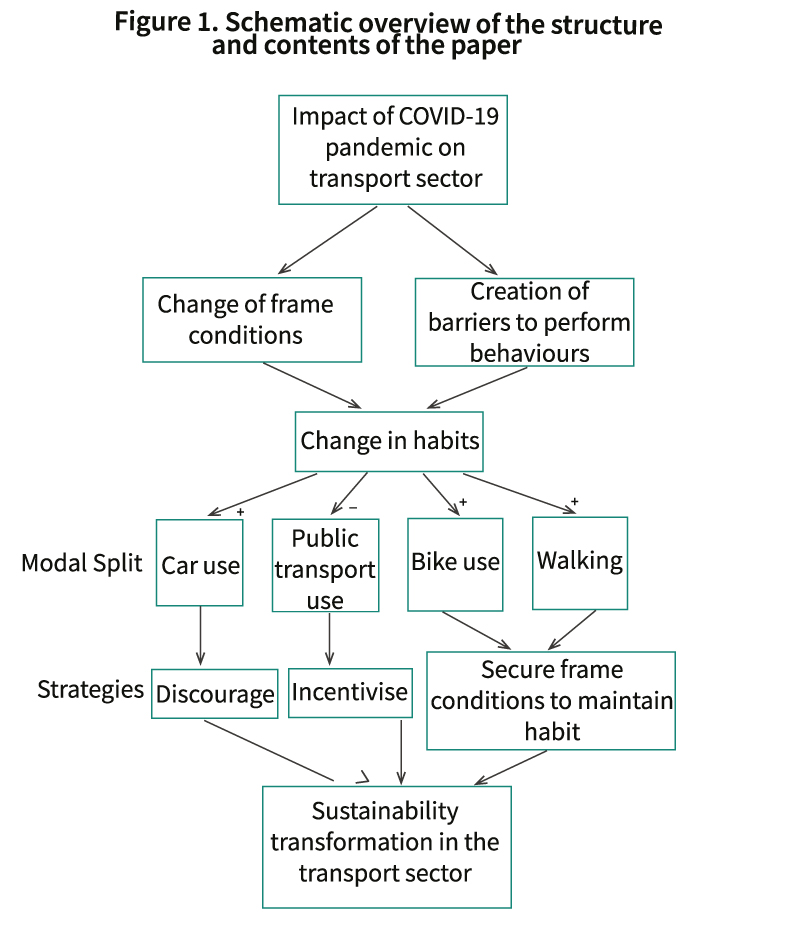

This paper aims to identify the opportunities that the pandemic brings about for a sustainable transition. It examines how the COVID-19 pandemic caused changes in individual habits in the transport sector. It furthermore explores which post-pandemic opportunities will arise to promote environmental-friendly situational parameters and behaviours that contribute to a sustainable development. Firstly, a theoretical background about habits will be provided. Subsequently, the transport sector and the associated habits will be presented from a pre- and post-pandemic perspective. The focus is then set on the windows of opportunity for sustainability transitions that emerged during the pandemic. In the following, an outlook on possible future developments of the newly established habits will be given. Finally, the main findings of the inquiry will be summarised, see Fig. 1.

Introduction to Habits

Habits are behaviours that are automatic, frequently shown, stable and that are followed by success3. They play an important role in everyday life. According to a study by Wood et al. (2002), about 35% to 53% of daily actions can be classified as habit. They allow to make routine decisions quickly and effectively without requiring many cognitive capacities4. Habits need about two to eight months to be formed after the behaviour was first shown5.

Previous research on how unsustainable habits can be disrupted shows that a change of frame conditions as well as the creation of barriers that prevent performing a habit is crucial6. The changes in daily life situations require new attention to former automatically executed behaviour. For instance, if a person habitually uses the car to reach the workplace, choosing the car as the mean of transport on the daily basis on the way to work is a less conscious process which is not reconsidered every single time. If the context changes substantially, for example after moving to a different city, a so called ‘Window of Opportunity’ for behavioural change emerges, and the transport mode used to commute to work needs to be consciously contemplated again7. In such a moment, the formation of a new habits is much easier than under unchanged life circumstances. Since establishing sustainable behaviours is a necessity for the mitigation of climate change, it is a key priority to identify and use such Windows of Opportunity to support sustainability transitions.

The Transport Sector and the Role of Habits

The transportation sector is the second largest contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally, after electricity and heat production. It currently accounts for about 16% of climate-damaging emissions, which include – most prominently – carbon dioxide, but also other climate forcers like volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) to name only a few 8,9. In the European Union, transport is even the greatest source of CO2, accounting for over a quarter of all greenhouse gases 10. After the EU succeeded to reduce transport emissions in the period between 2007 and 2014, emissions have been increasing again. Without consequent measures for reduction, national 2030 climate goals will be missed 10. This illustrates the strong need for rapid change within the sector. Adequate concepts and policies to approach this problem need to be developed and implemented promptly by scientists, practitioners and politicians.

Simultaneously, a change towards sustainable behaviours is required on the individual level. Personal transport makes up the bulk of total transport11. It is responsible for the majority of transport emissions, since the personal travel choices are in most cases unsustainable. In the EU, more than 60% of all CO2 transport emissions are produced by cars 12. Car drivers in Germany use their cars mostly for business-related travels (41%), during their holiday and leisure time (36%) and for grocery shopping (17%) 13. Most of these rides could also be managed by alternative, much more sustainable means of transport that would lead to a lower impact on the global climate. These include public transport, car sharing or, the least CO2 intensive options, travelling by bike or foot. However, the majority of the population still engages in unsustainable travel behaviours, leading to the continuous increase in emissions discussed above.

The travel choices individuals make are in many cases habitual. Regular transportation routes, such as the way to work, university or grocery shopping are most likely habitual since they involve repeated behaviours in a stable context. Accordingly, changing these habits towards more sustainable behaviour is an important leverage point for the reduction of GHG emissions. More specifically, a growing body of empirical evidence shows that habits play a major role in transport6. Findings from social psychology thus play an increasingly important role in complementing solution approaches developed in other disciplines, such as engineering, politics and environmental sciences. This emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to solve the complex problems occurring in the face of climate change.

Impact of COVID-19 on the Transport Sector and Associated Habits

The expansion of the COVID-19 virus to several countries in the world had a significant impact on the lives of the global population due to the necessary restrictions. March 16 in 2020 marks the date of the national lockdown in Germany. Many industries had to stop their production. Travel restrictions were imposed, and most people had to continue their work remotely in the home office. Global regulations of that kind led to a tremendous reduction in emissions. The sector that contributed to that reduction the most was the transport sector with a decline of -18.6% in ground transport and -43.9% for aviation and shipping emissions compared to 2019 in the first half year of 202014.

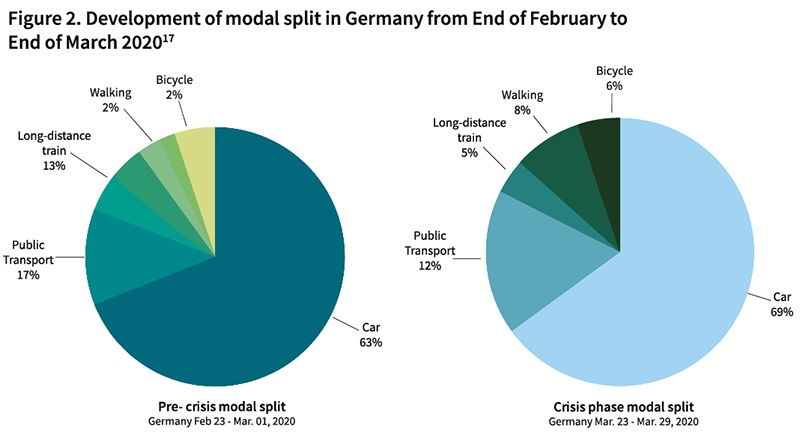

The great reduction of overall transport use was accompanied by a significant change in the modal split15. While sustainable commuting forms like public transport and shared mobility devices declined, individual car use became the preferred mode of mobility. However, also walking and cycling gained popularity and increased during the pandemic, which can be considered a positive development in terms of sustainability. In many cities, that led to the instalment of so-called popup lanes which were built to create more space for pedestrians and cyclists see Fig. 216.

As described above, it takes about two to eight months to form a new habit5. Given that the conditions of the pandemic prevail for now over a year, it is quite likely that the behaviours that emerged during the pandemic have now developed into new habits. When taking a closer look at the habitual changes in transportation, two different mechanisms likely have occurred. According to Klöckner (2005), habits break when either frame conditions change and/ or certain barriers prevent performing the habit6. The implications of the pandemic have brought about both, as will be explained in the following with the example of public transport habits.

People who would had normally used public transport to travel regular routes experienced a disruption of their habit with the outbreak of the pandemic. Public-transit ridership has fallen 70% to 90% in major cities across the world18. One reason for that is the change in frame conditions that was induced by the crisis. Since many people are required to work from home, they do not need to commute to their workplace anymore. Similarly, many places or events people would have normally visited are not accessible or taking place anymore due to the restrictions.

Another reason why many people do not use public transport in these times is because they associate it with low levels of safety and the risk of getting infected with the Coronavirus. The restrictions and the fear of infection can be considered as barriers that prevent the public transport users from performing their habit. As a consequence of these changes, new behaviours emerged. Instead of using public transport, many people shifted to traveling by car, bike or foot.

Window of Opportunity and Solutions

Currently, unsustainable behaviours such as car use are locked in as habits into the life of many citizens worldwide. As a matter of fact, habits are usually hard to change. However, as discussed before, schematically learned actions can be interrupted when people find themselves in a special or new life situation, such as a crisis6,19. Accordingly, the impacts of the pandemic could in fact have opened the window of opportunity to disrupt unsustainable travel habits and establish new, sustainable ones.

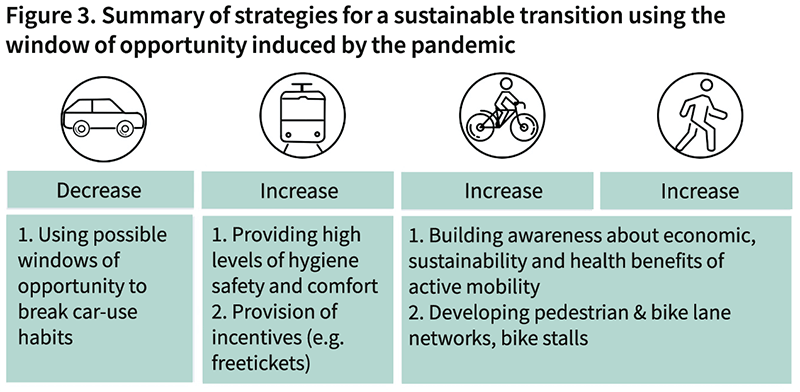

People could have potentially developed different habits with both negative implications for the environment (i.e., decreased use of public transport, increased car use) and positive implications for the environment (i.e., increased cycling and walking shares) habits. Newly formed habits that involve sustainable means of transport could be an important mechanism to support the sustainability transition of the transport sector after the pandemic – on the condition that they persist afterwards. Accordingly, gaining a deeper understanding about which conditions are required to preserve the habits beyond the era of the pandemic is crucial. Simultaneously, a strategy needs to be developed that leads car drivers to shift to public transport and other sustainable modes of transport. An elaboration on how this could be achieved, and which frame conditions and measures are required will be provided in the following section. A summary of the mobility measures is depicted in Fig. 3.

The end of the pandemic will most likely not happen as abruptly as the outbreak of the virus. It is, however, once again a time of upheaval that will lead to changing conditions in the daily life of the population. In order to encourage the establishment of sustainable habits, shaping the frame conditions for green transport modes in a way that people are encouraged to use them is of utmost importance in this period.

Reducing car use significantly is required for the reduction of emissions in the transport sector. Unfavourably, car-use habits are usually hard to change. The change of frame conditions that the pandemic has brought about could represent an opportunity to disrupt the car use habit. For example, with the prognosticated continuance of remote work after the pandemic, the demand for business-related mobility will be expectedly lower This process, however, strongly depends on whether car use can be successfully discouraged and whether sustainable modes of transport can be successfully incentivised in the future.

Public transit remains the backbone of sustainable transport, especially in urban areas. Accordingly, strengthening the approval of public transport again is a key priority. This can only be achieved by arranging favourable conditions for public transport users, such as high levels of hygiene, safety and comfort within the trains, buses, subways etc.15 Further needs of the local communities need to be assessed and integrated into transport policies in order to regain their trust in public transit.

A complementing approach could be the provision of a certain number of free tickets for public transport to users as soon as the pandemic circumstances allow it. Previous research shows that incentivising public transport use by providing free tickets for individuals that find themselves in a special or new life situation can be effective for increasing public transport use20,21. However, special attention needs to be paid that people who previously employed other sustainable travel modes such as cycling and walking do not shift to public transport as a consequence of the measure. Nevertheless, the combination of providing favourable frame conditions to regain trust as well as a monetary incentive in the form of free tickets in a new decision context has the potential to lead to an increase in public transport use after the pandemic.

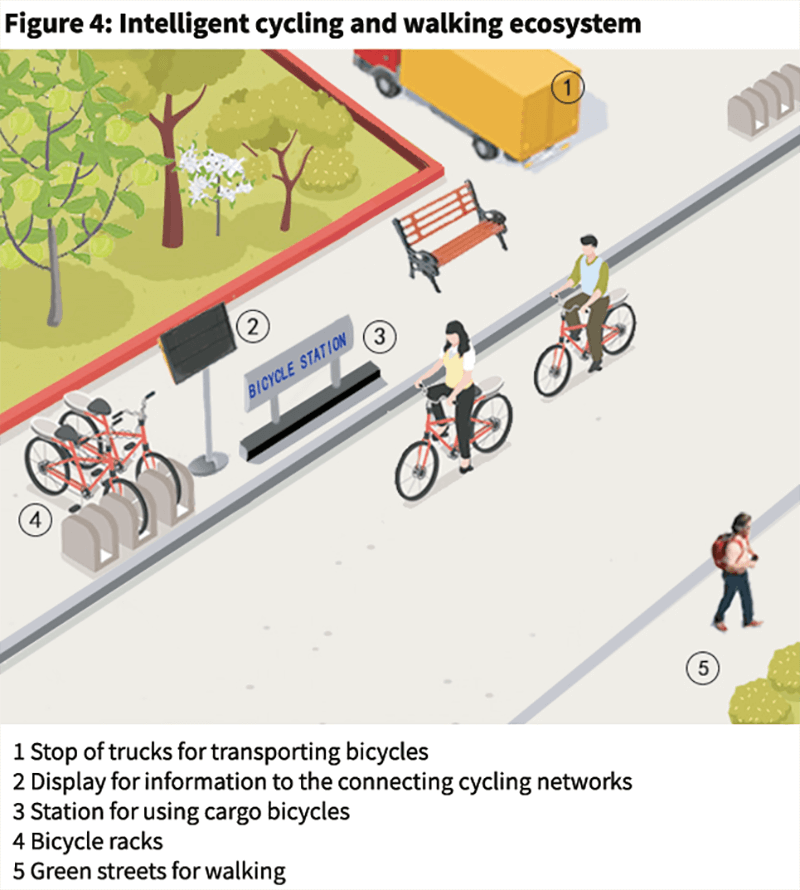

In accordance with these measures, it has to be ensured that people who had adapted new sustainable behaviours such as cycling or walking continue with this habit. Important frame conditions for this endeavour include a good infrastructure, such as a well-connected network of bike lanes. It is, again, crucial that cyclists feel safe when using their bike, see Fig. 4

The pop-up lanes that appeared in cities all over the world as a response to the increased cycling share represent important frame conditions for the preservation of cycling habits. If they would be abolished again, the change in frame conditions would pose a threat to the persistence of newly adopted cycling habit. It is thus highly advisable for policy makers to install these lanes permanently from a habit-preservation view. Fortunately, several local policy makers have announced plans to do so, among others London’s transport boss Andy Byford22.

Outlook

The further course of the pandemic and how it will impact mobility in the future is uncertain. However, taking a look at previous epidemic and pandemic events might help to estimate how the transport sector and the modal split might develop. A study by Beutels et al. (2009), about economic impact of the SARS epidemic in Beijing from 2002 to 2003 shows that at the peak of the infections in April 2003, public transport usage collapsed by over 60% 23. This is slightly lower but comparable to the decrease occurring in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In July – one month after the infection numbers had approached zero – the ridership for public transport got roughly back to normal 23. The SARS epidemic that started in South China soon developed into a pandemic that affected multiple other states. The severity of its impact is not comparable to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it shows us that the public transport is likely to regain its users once the pandemic comes to an end. For prognosticating the use of bicycles and walking as means of transport, information about the intention to use a certain mode may be serviceable. In a survey conducted by the ADAC in November 2020, 21% of participants stated that they will use the bike more often in the future. Even 27% stated that they intend to walk more often in order to reach their destination24.

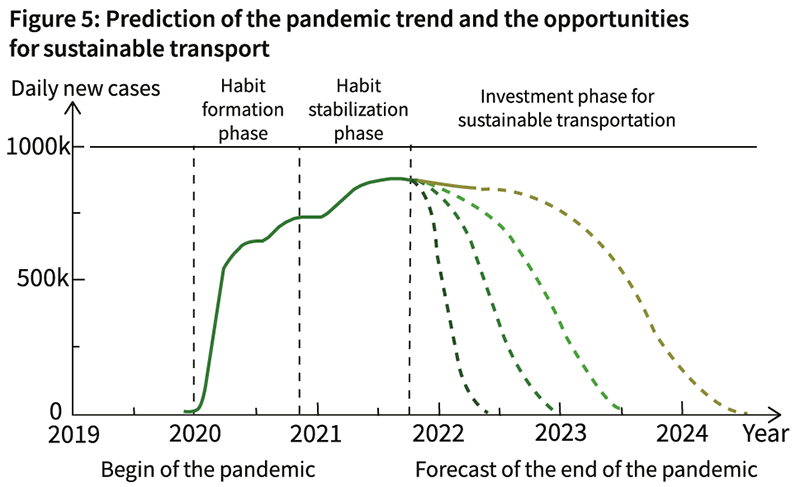

Since the COVID-19 pandemic presents us with completely new challenges, only rough estimates about future developments can be drawn. However, information of the kind that is presented above may help policy makers and transport organisations to adapt their strategies and take advantage of the opportunities that the pandemic brings about, see Fig. 5.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic induced a change in frame conditions that led to habitual changes of individuals in the transport sector. These new habits have the potential to accelerate a sustainable transition that is strongly needed for the mitigation of climate change and the protection of ecosystems and human well-being. As a result, it is of high importance to encourage individuals to maintain these new sustainable habits.

The emergence of new sustainable habits such as cycling and walking are beneficial behavioural shifts for a sustainable development. By securing physical frame conditions such as bike and pedestrian lanes, maintaining these habits beyond the pandemic era is encouraged. On the other hand, the use of public transport has tremendously declined globally while car use has increased. Consequently, robust strategies to regain ridership in public transit while simultaneously decreasing car use need to be developed. This poses a great challenge to scientists, policymakers and practitioners.

However, when the pandemic will eventually come to an end, a new window of opportunity will open. This will facilitate the change of unsustainable habits that have evolved during the pandemic, since frame conditions change again. By taking advantage of this upheaval, transitioning to sustainable modes of transport can be facilitated. Solution approaches like giving out a number of free tickets to incentivise public transport in combination with changes in life situation have already been proven to be effective20. Furthermore, experience from recent epidemics and pandemics suggests that the use of public transport will normalise again, once the infection numbers approach zero.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Maik Adomßent for years of support for the above seminar series in the Complementary studies at the Leuphana University Lüneburg, Germany.

About the Authors

Emma Saxena has started her bachelor studies in environmental sciences as a major and psychology and society as a minor at the Leuphana University Lüneburg in 2018. In 2020, she started her studies in the major psychology. She works as a research assistant for the three-year research project “Interplay of interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts as a barrier to sustainable settlements” funded by the German Research Foundation.

Emma Saxena has started her bachelor studies in environmental sciences as a major and psychology and society as a minor at the Leuphana University Lüneburg in 2018. In 2020, she started her studies in the major psychology. She works as a research assistant for the three-year research project “Interplay of interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts as a barrier to sustainable settlements” funded by the German Research Foundation.

Michael Palocz-Andresen has been working as Herder-professor since 2018, supported by the DAAD at the TEC de Monterrey Mexico. He became a full-professor at the University West-Hungary, a guest professor at the TU Budapest, the Leuphana University Lüneburg and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is a Humboldt scientist and an instructor of the SAE International in the USA.

Michael Palocz-Andresen has been working as Herder-professor since 2018, supported by the DAAD at the TEC de Monterrey Mexico. He became a full-professor at the University West-Hungary, a guest professor at the TU Budapest, the Leuphana University Lüneburg and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. He is a Humboldt scientist and an instructor of the SAE International in the USA.

References

- Gössling S, Scott D, Hall CM. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021;29:1–20. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Friedlingstein P, O’Sullivan M, Jones MW, Andrew RM, Hauck J, Olsen A, et al. Global Carbon Budget 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2020;12:3269–340. doi:10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020

- Steg L, Groot JIM de. Environmental Psychology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Newark: John Wiley & Sons Incorporated; 2019

- Wood W, Quinn JM, Kashy DA. Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1281–97. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1281

- Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, Wardle J. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010;40:998–1009. doi:10.1002/ejsp.674

- Klöckner CA. Das Zusammenspiel von Gewohnheiten und Normen in der Verkehrsmittelwahl–ein integriertes Norm-Aktivations-Modell und seine Implikationen für Interventionen. Bochum; 2005

- Schäfer M, Jaeger-Erben M, Bamberg S. Life Events as Windows of Opportunity for Changing Towards Sustainable Consumption Patterns? J Consum Policy. 2011;35:65–84. doi:10.1007/s10603-011-9181-6

- Sims R, Schaeffer R, Creutzig F, X. Cruz-Núñez, M. D’Agosto, D. Dimitriu, et al. Transport. In: Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, editor. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA; 2014

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Emissions by sector. 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector (March 03, 2021)

- Todts W. CO2 emissions form cars: the facts. Brussels, Belgium: European Federation for Transport and Environment AISBL; 2018

- Møller B, Thøgersen J. Car Use Habits: An Obstacle to the Use of Public Transportation? In: Jensen-Butler C, Sloth B, Larsen MM, Madsen B, Nielsen OA, editors. Road Pricing, the Economy and the Environment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2008. p. 301–313. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77150-0_1

- European Environment Agency. CO2 emissions from cars: facts and figures (infographics). 2019. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20190313STO31218/co2-emissions-from-cars-facts-and-figures-infographics (March 04, 2021)

- Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur. Verkehr in Zahlen. Flensburg; 2019

- Liu Z, Ciais P, Deng Z, Lei R, Davis SJ, Feng S, et al. Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun 2020. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18922-7

- Przybylowski A, Stelmak S, Suchanek M. Mobility Behaviour in View of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Public Transport Users in Gdansk Case Study. Sustainability. 2021;13:364. doi:10.3390/su13010364

- Laker L. World cities turn their streets over to walkers and cyclists. The Guardian. 11.04.2020;2020

- Mobility Institute Berlin. Modal Split before vs. after Outbreak, 23.1-1.3 vs. 23.3-29.3.2020 (Germany). 2020. https://www.covid-19-mobility.org/reports/update-calculation/

- Hausler S, Heineke K, Hensley R, Möller T, Schwedhelm D, Shen P. The impact of COVID-19 on future mobility solutions. 2020. https://www.mckinsey.de/news/presse/2020-05-10-mobilitaet-covid

- Louis MR, Sutton RI. Switching cognitive gears, from habits of mind to active thinking. Human Relations. 1991;44:55–76

- Matthies E, Klöckner CA, Preissner CL. Applying a Modified Moral Decision Making Model to Change Habitual Car Use: How Can Commitment be Effective? Applied Psychology. 2006;55:91–106. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00237.x

- Bamberg S, Rölle D, Weber C. Does habitual car use not lead to more resistance to change of travel mode? Transportation. 2003;30:97–108. doi:10.1023/A:1021282523910

- Stone J. Pop-up cycle lanes across London could be made permanent after pandemic, says transport boss. 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/cycle-lanes-london-pop-kept-after-pandemic-a9616041.html (March 05, 2021)

- Beutels P, Jia N, Zhou Q-Y, Smith R, Cao W-C, Vlas SJ de. The economic impact of SARS in Beijing, China. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14 Suppl 1:85–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02210.x

- Meyer H. Wie Corona Unsere Mobilität Verändert. Survey among 2145 German citizens older than 18 years. Results representatively weighed according to age and gender]. ADAC.[ 2020 (May 08, 2021)

- Worldmeter COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?fbclid=IwAR0tziIjfwC8mDXpsm8x8_iPF-QAdjOYmTez_VoTjewWjVShWRjRABT2Aq8 (May 15, 2021)